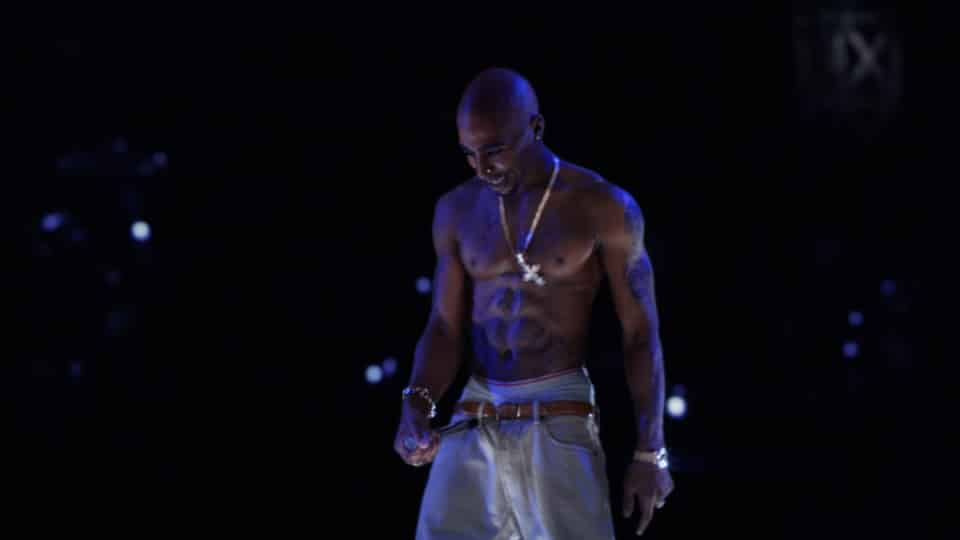

On day 3 of the 2012 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, onlookers were captivated by a computer-generated recreation of Tupac Shakur to perform with Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg. The animation used projection mapping in combination with a theatrical technique called “Pepper’s Ghost” to create a 3D holographic effect. The project employed a team of 20 artists, lighting designers, and technicians to create an unexpected, immersive audience experience.

Festival season is upon us, and with it comes more opportunities to showcase and explore interactive media. From music, to performance art, to technology-based installations, the event lead-up is a full-time engagement for artists, technologists, and festival organizers seeking to stand out in what has become a multi-billion dollar industry worldwide. Technology has hugely influenced festivals’ ability to engage audiences with interactive media. Where has this attraction for interactive and technology-driven media come from, and how is it impacting other public spaces?

Virtual Tupac at Coachella 2012

Interactive Media is Not A New Concept

Technological developments of the last half-century have breathed a new novelty into the concept of interactivity. Physically and emotionally participating in entertainment, which was the norm, became less common after the relatively recent advent of “passive” entertainment, like television and cinema.

“The reason we suddenly need such a word [as interactivity] is that during this century we have for the first time been dominated by non-interactive forms of entertainment: cinema, radio, recorded music and television.

Before they came along all entertainment was interactive: theater, music sport — the performers and audience were together, and even a respectfully silent audience exerted a powerful shaping presence on the unfolding of whatever drama they were there for.

We didn’t need a special word for interactivity in the same way that we don’t (yet) need a special word for people with only one head.”

—Douglas Adams, How to Stop Worrying and Learn to Love the Internet

Technology moved us away from interactive media, and ironically, technology is orienting us back to those original values when it comes to art and leisure—perhaps in an even bigger way than before TV. As much as technology has the power to isolate us, interactive media today is also more accessible, more invigorating on a multisensory level, and more likely to establish a genuine human connection than ever before.

Technology Has Revitalized Interactive Media

Using technology to create new forms of interactive media goes back to the mid-20th century. In the 1950s and 60s, Morton Leonard Heilig was one of the first to create VR in response to the passive experience of cinema.

“Without the active participation of a spectator, there can be no transfer of consciousness, no art.”

—Morton Leonard Heilig

Sensorama, which was patented in 1962, was a prototype for what he imagined would become “experience theatre.” It combined a stereoscopic 3D colour display, stereo sound, fans, olfactory dispensers, and tilted, vibrational seating to provide single viewers with a multisensory experience over the course of a short film. Heilig was unable to find funding to get Sensorama to industry players, and the project dissolved.

Morton Heilig’s Sensorama

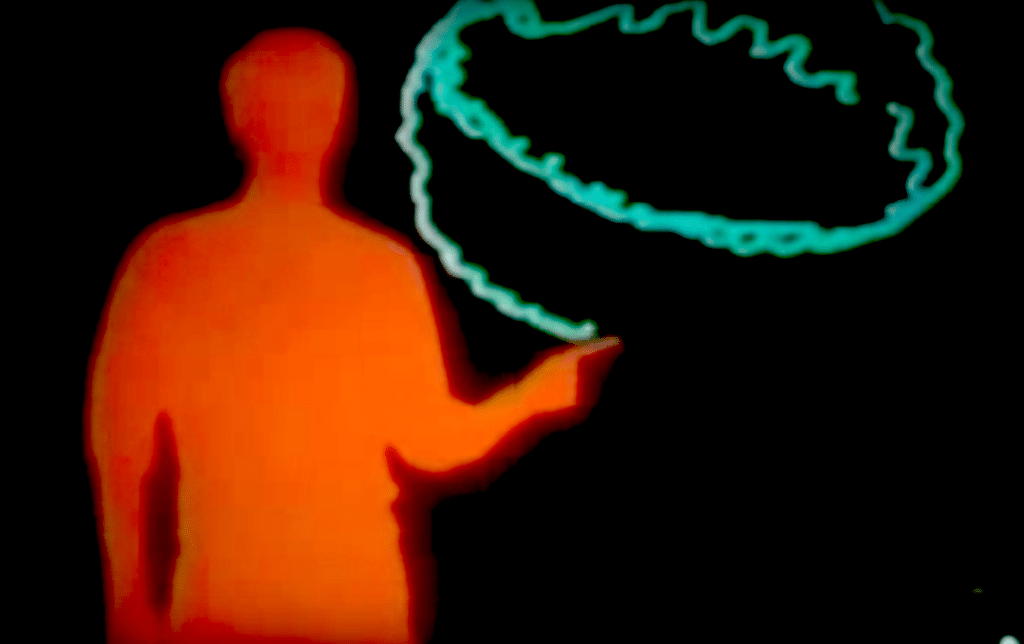

7 years later, Myron Krueger developed one of the earliest forms of computer-based interactive art. Glowflow was first installed at the University of Wisconsin’s Memorial Union Gallery. Pressure-sensitive pads were activated by viewers’ footsteps, triggering a real-time visual response from phosphorescent tubes and aural response from a Moog synthesizer. Glowflow was one of such interactive environments that lead to Krueger’s cornerstone project, Videoplace, in 1988. Videoplace is an artificial reality laboratory that creates reactionary light art out of viewers’ motion.

Much of Krueger’s work was motivated by a desire to redesign computers by addressing features that take away from an inherent human desire to connect and interact.

“There were things I resented about computers. I resented the fact that I had to sit down to use them. I resented the fact that I was using a hundred-year-old device to operate them—a keyboard—and the fact…that it was denying that I had a body of any kind, and that it was all perceptual, sort of, symbolic.”

—Myron Krueger

Myron Krueger’s Videoplace

Krueger modeled Videoplace after the relationship that artists and musicians have with their tools, seeking to create a type of computer that people could experience rather than use for the sole purpose of efficiency. The first rendition of Videoplace superimposed Krueger’s hand-drawn data tablet doodles onto a screen in the Memorial Union Gallery a mile away. The doodles would appear to interact with viewers’ shadows, which were also projected onto the screen in real-time. Almost by accident, Krueger noticed that viewers were most engaged when their motion appeared to create the doodles.

“We discovered that there was this very natural desire to identify with the image on the screen. Their image was them, and they expected it to do things in the video world as much as it did in the physical world. It was as if evolution had prepared us for seeing ourselves on television screens combined with computer images.”

Suddenly, here was a real, tangible example of how technology had the potential to bring human connection full-circle—back to what interactive media had done for us prior to the age of passive media. From VR to public art, interactive media has come a long way since Videoplace.

Burning Man: A Lasting Example Interactive Media’s “Rebirth”

Unlike static art, interactive media is unique by involving the viewer in its creation, forming a platform for human connection and community. Passive media is presented with the intention of presenting audiences with a static piece to derive meaning from, rather than involving their participation in the media’s creation and forming a community from that involvement. A good example of the rebirth of interactive media, especially as it relates to the growth of art festivals, is Burning Man.

On June 22, 1986, Larry Harvey and Jerry James built an 8-foot human figure out of scrap wood in their Noe Valley basement. They hauled the wooden man down to Baker Beach and quickly drew an audience of close to 40 people as flames engulfed the figure. Before you could say gasoline, the spontaneous hootenanny was singing a fire-themed tune on the fly, and a woman was literally hand-in-hand with the pyro-masterpiece.

“That was the first spontaneous performance…that was the first geometric increase of Burning Man. What we had instantly created was a community. And…you know if we had done it as an art event, people would have come, and come to the gallery or something, and said ‘It’s very interesting, perhaps a little derivative, what are you going to do next?’”

—Lee Harvey

The festival has since grown into a 70,000-person gathering based on the values of immediacy, participation, communal effort, radical self-expression and self-reliance, egalitarianism, and creativity—so unsurprisingly, the festival has become a global platform for the convergence of art and innovative interactive media, informing values within the tech industry (and perhaps vice versa). What began as a novel concept associated with underground movements became its own city with the power to impact the culture and values behind one of North America’s largest industries.https://player.vimeo.com/video/267460492?app_id=122963

Interactive Media’s Impact

Aside from influential Burners taking those core values back to the office after Labour Day each year, the impact of cultural phenomena like Burning Man has been a driving force behind the evolution of interactive media. Interactive media has re-infiltrated mainstream society, evolving in just a few decades from what was once associated with counterculture and festivals or niche, university-affiliated galleries like Videoplace.

Interactive technology and art are increasingly incorporated into civic space and public institutions like art galleries, science centres, shopping malls, and schools. Those behind designing and coordinating these spaces are realizing the advantage that interactivity has over passive forms of media in community building and increasing a return audience. Growing public values in interactive media are also expanding the tech industry, leveraging advances in interactive technologies like wearable tech, sound-to-light mapping, motion-tracking, VR and AI.

Montréal’s Impulse — dezeen.com photo

Passive media is still the norm for a culture built on Netflix. But the values behind traditional forms of interactive media has been experiencing a rebirth over the last few decades, thanks to innovators like Myron Krueger and events like Burning Man—and the technology behind our ability to realize those values is growing every day.