Limbic Media’s Project Technical Lead, Jason Sanche, recently wrote about Aurora in a paper for a university course on Neuroaesthetics. Jason is finishing his Computer Science degree at the University of Victoria and couldn’t have timed this article better with our recent posts about multisensory technologies and their effect on brain development and behavior. The following was adapted from a series of papers exploring perceptual experiences inspired by the artists’ discoveries and insights with specific artworks, and in this case, Aurora.

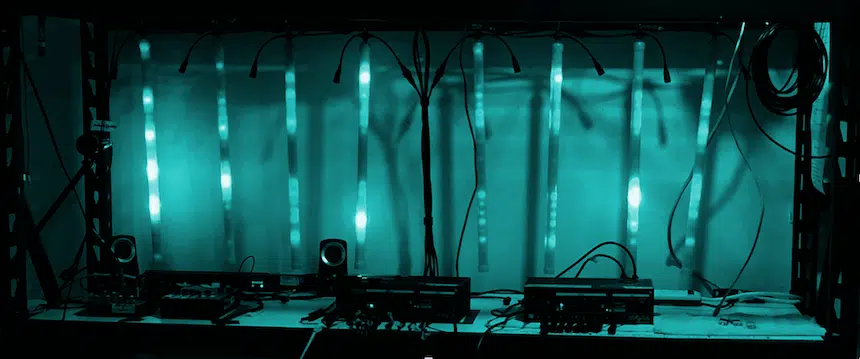

Aurora QA Station

Aurora: An Exploration in Perception

This article is an exploration of my perceptual and aesthetic experience of Aurora, a software platform developed by Limbic Media to map intricate sound qualities to light. Aurora listens and recognizes subtleties of sound and displays sound as patterns and shapes within two- and three-dimensional matrices of LED light. Aurora elegantly visualizes music with the subtlety of a musician’s ear.

Sounds have incredible texture, depth and emotional resonance, but these facets of sound often go unnoticed. Input from other senses, thoughts, and emotions, especially with the proliferation of screens, continually eclipses our simple awareness of sound. Subtleties get sublimated into the background of our experience. However, the act of listening attentively realigns the mind with time in a constant, steady, somatic-acoustic present awareness. By showing sound as light, Aurora leverages the domination of visual stimuli and brings attention to sound.

Aurora’s hardware technology is, as Marshall McLuhan would say, an extension of our senses. In the same way, Aurora’s software is an extension of our minds and its neural and perceptual networks. Aurora performs similarly to synaesthesia—a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. We naturally create images when hearing sounds, which might be an inherited survival trait to anticipate danger from threatening sounds. Incredibly, it also applies to appealing sounds like beautiful music. With our eyes closed and our attention narrowed in on music and the field of mental images, a synaesthetic effect involuntarily transforms sound into mental imagery. Aurora extends this phenomenon into shared space.

The following is a subjective exploration of this idea as a written stream of consciousness about the experience of Aurora reacting to a piece of music:

As the music streams from its digital storage on a cloud of distributed data into the physical network of this room, through my computer, through the mixer and into Aurora which, in real time, processes the signal through digital filters, determined by code, transformed into patterns and colors imitating the harmonies, rhythms and beats, transmuted into bursts of photons varied by a full visible spectrum of color and coordinated patterns with the complexity of the wave patterns in the ocean and captured by my eyes, translated in the optical nerve back into electrical impulses, and again, in real time, perceived as what I believe is sentient to the experience and understood as meaningful. As I write and watch the dancing lights, making the music more beautiful, I perceive and write and know this harmony of embodied sensory experience augmented by technology-as-art.

The study of neuroaesthetics looks at how the mind perceives and attaches meaning to art, beauty, and ugliness, how we fixate on and identify value, and how art produces emotional reactions. A system like Aurora provides a rich and fascinating angle to explore interactivity in neuroaesthetics, and specifically how the perceptual feedback of sound visualization plays into the brain’s implicit synaesthesia.

When sound-to-image happens externally, how does that affect our internal imagination of sounds and music? How important is sound-to-image synaesthesia to our ability to thrive culturally and socially? Can technology like Aurora produce a shared synaesthesia similar to shared public experiences during a film, concert or theatre performance? In participatory public theatre like Sleep No More, the play creates an immersive experience by breaking down divisions between actors and the audience. Can Aurora similarly produce immersive shared participatory musical synaesthetic experiences? The potential is there.

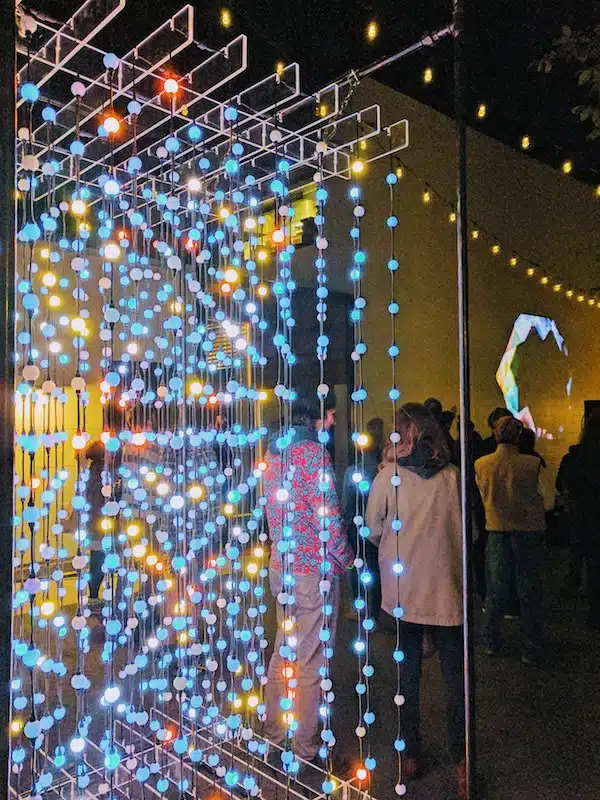

Innovation Tree, Victoria, BC

Art’s Role in Imagined Embodiment

Imagined embodiment has been a common theme throughout my explorations in perception. The mind constantly reinterprets its sense of self and embodiment in the world through imagination and dreaming, and the habitual sense of self is usually reinforced if we are unconscious of this process. However, with the right attention and tenacity, we can have full control over our self identity and full freedom from its limiting influence on our inhibitions. Anyone can imagine themselves as anything or anyone, and with enough practice, anyone can act beyond their usual identity. Most people enjoy an occasional respite from the trappings of their identity through events like halloween, masquerade parties, games, and to some extent, books and films that transport us into characters we can safely identify with.

One important role of art is to challenge and disrupt habitual identity through the perceptual experience of imagined embodiment, and made possible by mirror neurons. Conscious engagement in this process through art can introduce viewers to new horizons in self-knowledge.

PGNB Prismo 2017

Interactive Digital Art and Synaesthesia as a Method of Embodiment

The most relevant method of imagined embodiment to Aurora involves the exploration of synaesthesia. Synaesthesia is a unique doorway from the visual to the aural. If we pay attention to sound and its effects on the imagination, it has the potential to create a transformative experience and disrupt habitual sensory perception. Experiencing synaesthesia consciously by meditating on music or sound and absorbing mental imagery restores attentive listening and its meditative benefits. Interactive digital art like Aurora uses technology to leverage synaesthesia and bring audiences back to the present through attentive listening.

Aurora’s lights react to sound the way our mind would visually imagine the source of any sound. The nature of sound and the act of listening have a unique quality that visual perception does not—sound disappears nearly as soon as it is heard; it is more ephemeral and decays quickly through friction unlike most visual objects, which tend to persist until they are destroyed, or decay over longer periods. Because sound does not persist very long, attention to sound created a synchronization to the ineffable flow of time: the steady, consistent arising and dissolving of the soundscape. By perceiving sound as light we tune into the act of listening which is an important way of staying balanced and present in a sensorially fractured world. This allows the mind to be present in time, which is its natural state.